In a recent visit to Amazon headquarters in Seattle, Stadium Tech Report got a “inside look” in Amazon’s labs, where a whole host of technologies, including artificial intelligence, edge computing, 3D modeling, motion-tracking software and good old-fashioned learned experience is informing the future of the company’s technology that lets customers quickly purchase items without having to “check out” with a human or a terminal. Amazon also gave us a how-it-works demonstration of the company’s newer RFID-based store technology, which is already being used at team merchandise stores in several pro stadiums.

We also got some very strong confirmations from Amazon executives that the still-spreading rumor that claims that the stores are actually using live humans in India to record what shoppers are doing is not true.

“It’s just outright false,” said Jon Jenkins, vice president of Just Walk Out for Amazon, about the humans-watching-videos rumor. What is true is that in the wake of Amazon removing Just Walk Out from its larger Amazon Fresh grocery stores, the company is going to put more effort behind getting the technology into smaller, more focused stores, like stadium concession stands, as well as airports, convention centers, hospitals and campus locations.

Focusing on the verticals that work

In an April 17 blog post on the Amazon site, Dilip Kumar, Amazon’s vice president for AWS applications, wrote about the rumors and gave an update on where the company is heading with Just Walk Out, a business that is part of the AWS entity.

“We have strong conviction that Just Walk Out technology will be the future in stores that have a curated selection where customers can pop in, grab the small number of items they need, and simply walk out,” Kumar wrote. “In fact, the response from shoppers to Just Walk Out in small-format stores has been so strong that we will launch more small-format third-party Just Walk Out stores in 2024 than any year prior, more than doubling the number of third-party stores with the technology this year.”

During our mid-June visit to Amazon’s downtown Seattle offices, which was hosted by Jenkins, we learned exactly how the Just Walk Out stores solve the “hard problem” of determining which items customers are selecting, and how Amazon is looking to keep innovating to make the stores less expensive to build and operate. While we were not allowed to take any photos or quote engineers by name, we did get to see how the stores are actually built and operated, and heard of a number of complex challenges which the Amazon engineers are continuously trying to solve in better, faster and cheaper ways.

We also heard more details about the RFID store technology, which fits into the sports vertical nicely and solves problems with merchandise that camera-based technology can’t handle. As we found out, RFID stores have their own set of growing pains but also offer great potential not just for stadiums but also for entities like touring entertainment acts, who might be able to carry their merch-store technology with them from venue to venue.

Behind the scenes: How Just Walk Out actually figures out what you bought

If there is a reason why the “it’s really just people watching on video” meme is persisting, it could be because on its face, the premise of checkout-free technology is still a hard thing for many people to believe. Even though stores from multiple providers have now been open and working for several years, it’s a safe bet that the majority of shoppers in the world still don’t quite understand just how a bunch of cameras and sensors can accurately track what anyone is randomly purchasing, even in a small-sized store. But the technology from Amazon and its competitors does work, and has already accounted for millions of transactions.

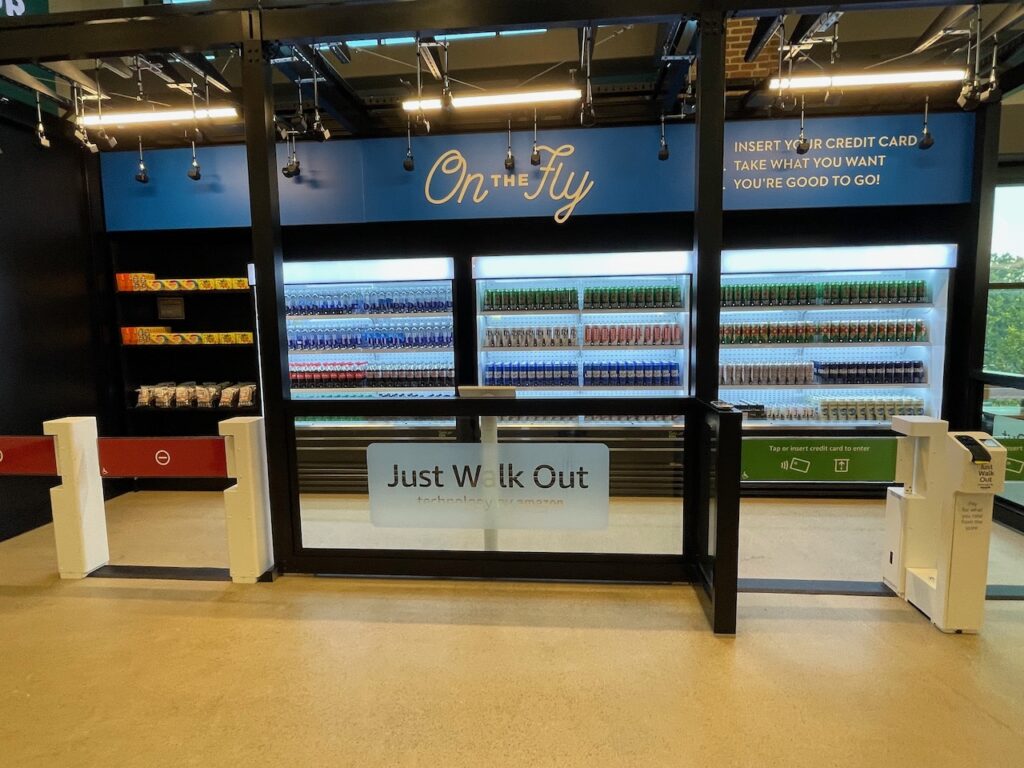

If you’re not familiar with checkout-free stores, here’s a quick primer. Customers are allowed to enter gated stores by scanning a credit card or some other pre-authorized payment method (including biometric methods using faces or palms). After entering they simply take the items they want and then exit. Using technologies including cameras and (from some providers) sensor shelves, the stores can automatically detect what items customers are selecting. Payment takes place online after they leave the store.

Amazon’s Jenkins said that the genesis of Just Walk Out came from some mid-2010s-era discussions about how Amazon could make retail shopping easier, a thought process that identified checkout lines as one of the biggest pain points. Though self-scan checkout systems had already been developed, Jenkins said “that just took the retailer’s problem and made it the customer’s problem.” So Amazon decided to do “something with the whole notion of checkout,” and after thinking about and testing various options of camera and sensor placements to see if they could be combined to replace traditional checkout systems, the first version of a Just Walk Out store was opened by Amazon’s own retail group in 2018.

“There was a huge line outside the store before it opened, and the technology actually worked,” Jenkins said.

By 2024, the technology has matured, and while it has not proven to be a fit for bigger cart purchases at traditional-size grocery stores, in smaller, more time-critical deployments checkout-free technology from the leading providers is growing rapidly.

According to our unofficial tally of the stadium-specific checkout-free market, there are approximately 185 known checkout-free concession stands in stadiums, with many more planned to debut later this year. Alongside Amazon, which has 74 Just Walk Out stadium stores and five RFID merchandise stores, the top players include Zippin, a San Francisco-area startup with 85 stadium stores open, and AiFi, also a Bay area startup currently with 26 operating stadium stores that will be joined by 40 or more stores when its stadium-wide deployment at the Intuit Dome in Los Angeles opens later this summer.

So how does something that seems somewhat impossible actually work?

According to the two Amazon engineers who showed us technology demonstrations, some of the parts of the Just Walk Out technology mix are actually well understood and not extremely difficult to deploy. Take the motion-detection software, which tracks a customer — or a group of people shopping together — as they wander through the store. Using detection points on heads, feet and hands, the engineers said that the software they built makes the tracking “a well-solved problem,” and is somewhat similar to self-driving technology that helps guide cars.

What also makes the systems work easier are predictable store layouts with smaller numbers of discrete items. At Amazon, stores are laid out with 3D maps that help the cameras figure out where customers will be standing, and a store’s available merchandise list is synchronized with those maps so that for the most part, the system knows what should be in a certain place in the store at any given time.

The “hard part,” as the engineers told us, is the actual shopping part, where customers physically choose an item from the drink coolers or from product shelving. Even as Amazon has learned over the years how to better mount cameras to get the clearest looks possible, the infinite random possibilities on how people shop create the toughest thing for the stores to get right.

The engineers pointed out some of the hurdles with a video “test,” where we watched a person selecting items and had to guess how many were purchased. My guess of one item was incorrect, as the “shopper” actually grabbed two similar items with one hand in one motion, something you had to view a few times before you could really see what was happening.

The degree of difficulty in determining what was selected gets higher, such as when customers select one item and then put it back, sometimes not in the place they got it from. Other things that can make the process harder include cooler doors that get fogged with condensation, or customers reaching behind the first item to get “a colder drink” from farther back in the cooler.

But by splitting a customer’s stay into what Amazon calls “space-time tokens” of little slices of video from multiple camera angles, it can build a trackable list of actions that let the store’s system determine what the customer may be doing. That list then gets analyzed by the artificial-intelligence model to determine if a customer has actually selected an item, and then to charge them for an item that can be confirmed (as best as possible) by the combination of inputs including a video image of what the item is, where it is located in the store, and how the customer might be holding it.

Unlike language AI like ChatGPT, Amazon’s system is not learning words and phrases. Instead, it is learning how people act when they shop, and is building its own model on information gleaned from initial Amazon inputs plus from every shopper who buys something in the system.

“The model understands what the person is doing — picking an item, and putting it back. It has learned what that looks like,” one engineer said. “It can localize space and time with deep understanding.”

But what makes Just Walk Out (and other checkout-free technology) so much harder than other AI systems, Jenkins said, is the very small tolerance for error.

“If you’re using AI for search, most people are smart enough to easily correct bad results,” Jenkins said. “There’s a human filter.”

But for retail operations, Jenkins said, “we don’t have that luxury — we need a correct receipt. Customers and credit card companies do not get happy with you if you have incorrect receipts. In this case, 90 percent is not good enough.”

According to all three of the top checkout-free technology providers, using real humans to closely review and correct and annotate video replays of actual difficult shopping events is necessary to keep teaching and improving the AI models so they make the best choices first. But to make the stores work in real time, it’s the combination of all the technologies that allow checkout-free providers to deliver very high accuracy (all of the vendors in the space claim their accuracy on getting orders correct is in the 98-99 percent range).

RFID: An old technology turns a new trick in the customer’s favor

While packaged goods like cans of beer and boxes of popcorn work extremely well in camera-based checkout-free stores, there is one category of retail — team merchandise — that does not.

Consisting mainly of jerseys, sweatshirts, t-shirts and hats, team merchandise does not lend itself well to being identified by a system of cameras and sensors for two main reasons. One, because soft goods like clothes don’t hold a shape, it’s extremely hard to differentiate between goods simply by looking at them. Second, because clothing comes in many different sizes, it is near impossible to determine what size a customer is purchasing without looking closely at a label. And since fans almost always want to try a piece of clothing on to see if it fits, putting soft goods into boxes won’t work in a stadium setting.

Because of the high margins on something like a $250 special jersey, team merchandise stores are a great stadium business — but they are also responsible for maybe the longest lines at many events. Fans at big-name tours for acts like Taylor Swift or BTS regularly spend multiple hours in lines to purchase “merch,” a problem that both customers and providers of the goods would like to eliminate.

One new idea being tested by Amazon as well as some startup tech suppliers is to use Radio Frequency Identification, or RFID, as a checkout technology. A longtime staple of retail stores for inventory control and theft security, RFID is now being looked at as a way to let fans select and buy team gear in a faster way, by letting an array of RFID antennas indentify and charge customers without staff having to ring up items one by one.

The premise for RFID-enabled stores from Amazon involves using some of the newest RFID labels (which are basically just a thin strip of metal) that can either be sewn into or attached to item price tags. In Amazon’s stores, fans enter a store area without providing any payment information, and can try on or even put on gear they intend to purchase. When they are ready to check out, they exit through a store gate that has credit-card scanners and a group of RFID antennas.

(Even though the experience is technically not a “just walk out” process in the strictest definition of the phrase, Amazon includes the RFID stores under its “Just Walk Out” branding umbrella given the speed of the process.)

Once a customer scans a valid payment method, the antennas search for any RFID-labeled goods, and total up a bill that is charged to the card. The customers then simply walk out, without having to talk to a staffer or wait to have their items totaled manually. (Other RFID stadium gear stores, like some from a startup called Retailcloud, use counters with self-serve checkout “buckets” with RFID antennas to identify items.)

Jenkins noted that while RFID has been used widely in the past for inventory and security purposes, this may be the first time the technology has been deployed primarily for the benefit of the customer. By putting all the technology at the end of the process, Jenkins said Amazon has made it easier for customers who might not end up buying anything.

“At the merch stores we don’t force you to give your credit card information when you come in, because you might just be browsing,” Jenkins said. “If you don’t buy anything you can just leave, which makes it better for the user.”

The checkout “gates” Amazon deploys at its merch stores (in the past year Amazon opened single stores at Lumen Field in Seattle, Globe Life Field in Arlington, Texas, Hard Rock Stadium in Miami Gardens, Fla., Inter & Co stadium in Orlando, Fla., and Children’s Mercy Park in Kansas City) usually have two lanes, with each one containing multiple RFID sensor antennas. There are also RFID antennas overhead, mounted in a kind of tent-like structure.

As fans approach the gates they enter payment information via the attached device; then after their products are sensed they exit through the gates, with a bill presented later online similar to how Just Walk Out stores process payments. Customers can even put on the gear and wear it while checking out, a process Jenkins demonstrated by putting on a red plaid “Elmer Fudd” type hat and wearing it while he “checked out” of the store in the lab demo area.

According to Amazon, the stores performed quite well last year, especially at Globe Life Field where the Texas Rangers went all the way to become World Series champions — creating many opportunities for fans to purchase playoff gear.

What has stoked a lot of interest in the RFID stores, Jenkins said, is the portability of the exit-gate technology, which doesn’t need to be permanently mounted. (Jenkins said Amazon is working on a version of the gates that could be more mobile, perhaps with wheels attached.) That easy portability could allow for traveling acts to possibly bring RFID store technology with them on tours, to set up in tents outside each arena. Since the concept also doesn’t depend on an array of mounted cameras, stores can be any size, Jenkins said. The Lumen Field store, for example, was a “pop-up” type variety, staged on an empty concourse area.

While some product suppliers are already pre-tagging gear with RFID labels, Jenkins said teams and venues can easily add the tags themselves. On the back end, the RFID technology performs another valuable trick in allowing for easy inventory, since racks of hanging clothes can be simply scanned by a staffer carrying a handheld RFID “gun.”

Since RFID is an antenna-based technology, the store systems do have to deal with issues of interference and random signals. One problem the Amazon engineers showed us involved the closeness of the two checkout gates, a placement Jenkins said was necessary from a store flow standpoint. Becuase the gates are so close, antennas from one gate can sometimes “see” RFID items from the other gate. The engineers showed us, however, that the system can determine which item is closer by checking the signal strength, giving a higher confidence that each gate is totaling up only the correct items.

The antenna-proximity issue also reared its head in a couple of early store deployment issues Jenkins told us about. In one, a trash can just outside the store exit proved to be a popular place for customers to discard their price tags — making it a hotbed of RFID signals that the gates could still “see.” Another issue came up from a rack of shopping bags that was placed just before the exit gates to give customers a way to possibly carry their items around — an idea that didn’t work well since the checkout gates could “see” all the tags on the numerous bags hanging on the rack.

But Jenkins has high hopes for the RFID stores, which could provide new ways to get fans merchandise more quickly, especially in places like PGA Tour stops which might not have permanent store structures, or for popular tours like Taylor Swift which might not be able to hire enough people for enough hours to satisfy fans’ demands for merch.

“It opens up a whole new world,” Jenkins said.

Where will Amazon take Just Walk Out?

Internet rumors aside, the next question for Amazon and Just Walk Out is where and how far the company will push the technology. One area Jenkins said Amazon is aggressively addressing is the cost of deploying stores, something cited by many stadium and venue operators as the reason why they have held back on deploying checkout-free stands.

By improving its systems, Amazon’s most recent store deployments are actually using far fewer cameras than its first versions of Just Walk Out, Jenkins said. Amazon is also working on offering more smaller versions of Just Walk Out stores, like versions that can be deployed simply into exisitng concession stands without much renovation work. Zippin, which still leads Amazon in the total number of stadium-based checkout-free stores, has been very adept at introducing smaller, easier-to-deploy versions of its checkout-free stores, which have proven to be very popular.

The other main competitor in the space, AiFi, is set to get a big boost when the Intuit Dome, the new home of the Los Angeles Clippers, opens later this summer. Last week, AiFi announced that it is supplying the technology for more than 40 checkout-free concession stands at Intuit Dome, which will give both the company and the technology a big spotlight in the public eye.

While he wants Amazon to succeed, Jenkins told us earlier this year in a podcast that store wins from other players in the market only help to validate the whole idea of checkout-free retail. And unlike the two other companies leading the stadium space, Amazon doesn’t really have to worry about finding venture-capital funding or more employees to survive.

“I’ve got an army of engineers working on this,” Jenkins said.